Chapter 64

It's a new century, a new millennium, and in many ways a brave new world. As elegant and essential as smoking was throughout the 20th century, the hard, cold fact is that it isn't socially tolerated today. And perhaps that's not altogether a bad thing. As we saw last week, smoke and ash pose specific issues detrimental to clothing and dressing well. Tobacco has run its course, it seems, and it appears that the effects of a century of gross overindulgence have closed the door for good.

Puffing a pipe or rolling a cigarette isn't seen as the innocent indulgence it once was -- it is more likely seen as an affront to society, akin to pulling a gun on the poor fellow sitting at the next table. An over-cautious and somewhat reactionary populus sees smoking as a grave health concern not just to the smoker, but to the smoking-adjacent as well.

Obviously, a new pastime for the well-dressed adult needs to be found; one that both fulfills the role that tobacco has played for five hundred years, and at the same time addresses its adverse issues. In fact, such an item already exists, albeit in its embryonic form. It is rather inelegantly called the "electronic cigarette."

E-cigs have been around for about ten years, surrounded by a mix of mystery, suspicion, and mis-information. Rumors abound concerning just what they are, and the FDA is puzzled as to just what to do with them.

Let's crack the mystery, lay bare just what this new bit of tech is, dispel the myths, and discover why this just may be the new Essential Accessory for the twenty-first century!

What we know today as the "e-cigarette" was invented in April 2000, by a pharmicist and inventor in Beijing named Lik Hon. When his father died of lung cancer after a lifetime of heavy smoking, so the story goes, Mr. Hon developed a device that looks like a cigarette, acts like a cigarette, and feels like a cigarette, but without any of the carcinogens of combusting tobacco. It was patented in China as an "Aerosol electronic cigarette." The inital American patent was filed in May 2007 as an "Emulation aerosol sucker," and was elaborated upon and expanded in his U.S. patent filed November 2010 as an "Electronic atomization cigarette." The amount of nicotine delivered can be varied, weaning the smoker off of his addiction. The company he works for, Ruyan, produces and markets them. A few rival companies began producing their own versions soon after; but all commercial e-cigs are made in China by these few companies, and are re-branded by thousands of re-sellers worldwide.

E-cigs are commercially produced in several sizes and forms, from sub-cigarette up to cigar size, and even a pipe shape. Regardless, they all work on identical principles: a small nickel-metal hydride rechargeable battery powers a small heating element made of coiled nichrome wire. This wire (the atomizer) is in contact with a wick soaked in the working fluid. This fluid is heated to its vaporization point, and this vapor is the carrier that is inhaled. The fluid is replaced by disposable cartridges as it is depleted.

Several things are immediately apparent even with this bit of information. First, this is not a cigarette in any sense of the word. It contains no tobacco, does not combust anything, and does not produce smoke. In fact, even calling it an "electronic cigarette" adds much to the confusion surrounding the technology. Some new terminology has thus arisen: those "in the know," (and that's you, now,) call it a Personal Vaporizer, or PV. The lingo works like this: Smokers produce smoke by smoking cigarettes -- Vapers produce vapor by vaping PVs. Simple, right?

Another misconception is that a PV's working fluid is some sort of "liquid nicotine." Actually, it's nearly entirely propylene glycol, with a tiny (and variable) amount of nicotine and flavoring added to it. Vaporized propylene glycol is in fact the very technology that is used in fog machines; so this is not tech that is breaking any new ground -- merely its utilization, and its battery-powered miniaturized scale.

Let's look at propylene glycol for a bit -- it has an interesting history, it's at the heart of the PV, and it holds some fascinating surprises.

Also called 1,2-Propanediol or C3H8O2, propylene glycol is a very versatile substance, used as a food preservative, an additive for food colors and flavorings, a solvent for medical preparations, a moisturizer, and a carrier for perfume oils and soap bases. Its pharmacokinetics show it to be also quite safe. It is metabolized in the human body largely into pyruvic acid and converted to energy. Propylene glycol does not cause sensitization and it shows no evidence of being a carcinogen or of being genotoxic.

But that's nothing compared to a discovery made in the late 1930s, that it was also a very effective germicide!

A study at the University of Chicago by Drs. O. H. Robertson, Edward Bigg, Theodore Puck, Benjamin Miller, and Elizabeth Appell, called THE BACTERICIDAL ACTION OF PROPYLENE GLYCOL VAPOR ON MICROORGANISMS SUSPENDED IN AIR proves the germ-killing properties of propylene glycol, and is very interesting reading for the technical-minded.

Time magazine ran the story, called "Air Germicide," on Nov. 16, 1942. It reads, in part:

"A powerful preventive against pneumonia, influenza and other respiratory diseases may be promised by a brilliant series of experiments conducted during the last three years at the University of Chicago's Billings Hospital. Dr. Oswald Hope Robertson last week was making final tests with a new germicidal vapor — propylene glycol — to sterilize air. If the results so far obtained are confirmed, one of the age-old searches of man will finally achieve its goal...

The researchers found that the propylene glycol itself was a potent germicide. One part of glycol in 2,000,000 parts of air would — within a few seconds — kill concentrations of air-suspended pneumococci, streptococci and other bacteria numbering millions to the cubic foot...

Dr. Robertson placed groups of mice in a chamber and sprayed its air first with propylene glycol, then with influenza virus. All the mice lived. Then he sprayed the chamber with virus alone. All the mice died...

Propylene glycol is harmless to man when swallowed or injected into the veins....Last June, Dr. Robertson began studying the effect of glycol vapor on monkeys imported from the University of Puerto Rico's School of Tropical Medicine. So far, after many months' exposure to the vapor, the monkeys are happy and fatter than ever. Dr. Robertson does not expect mankind to live, like his monkeys, continuously in an atmosphere of glycol vapor; but it should be most valuable in such crowded places as schools and theaters, where most respiratory diseases are picked up."

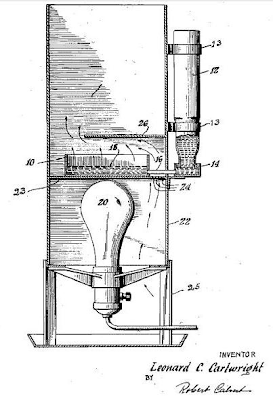

Dr. Robertson took out the patent on the method of sterilization of air by vapors in November 1943. The above illustration is the method of vapor production used in the initial experiments. One can easily discern the key components of the modern PV even at this early stage: the syringe acts as the cartridge, the atomizer (as today) is the wick wrapped in an electric heating element. Air is drawn over the atomizer, mixing with the vapor, and into the test chamber.

Propylene glycol was planned to be used in large-scale air disinfection in hospitals, until it was discovered that ultraviolet light gave the same result...and it was much easier to wire up a simple light, than devise a system to pump vapor through an HVAC system. So the concept wasn't pursued, although Dr. Bigg patented an apparatus that did just that in March of 1944. Glycol and water were heated to their vaporization points together in a tank by an immersion coil, providing humidification as well as sterilization. Since water and glycols vaporize at different rates, an ingenious device using a thermoswitch automatically regulated the water to maintain the concentrations in equilibrium.

In 1946, he filed a patent for an improved distribution system, which wasn't issued until 1950. In this version, the glycol is vaporized indirectly: instead of direct contact with an atomizer, glycol is fed at a controlled rate onto a series of baffles in a branch line of ductwork. The air in the branch line is electrically heated to vaporization temperature, and is drawn up past the baffles by way of a venturi in the main duct, vaporizing the glycol as it passes.

In March 1950, Leonard Cartwright patented a method of localized vapor production that began to look like a large version of a PV. In fact, it is by very definition a "personal vaporizer." In this instance, the propylene glycol is fed from an exterior reservoir into a shallow dish, that is in contact with an incandescent light bulb and heated to vaporization temperature. Convection currents draw air over the dish and up the chimney, ostensibly into a hospital room. Apparently it worked very well; the inventor makes mention of the visible "fog" that it produces.

In August 1965, Herbert Gilbert patented a design for a "smokeless non-tobacco cigarette," that at first blush would seem to be the progenitor of the modern PV. In fact, many people mention this patent in the same breath with PVs, which is why I'm including it here. It isn't related to the modern PV, though. Instead of the atomizer/glycol arrangement that is at the heart of a PV, this design used a long, thin incandescent bulb or vacuum tube (!), rather improbably powered by a tiny button-cell battery to merely heat the air that has passed over a saturated "flavor cartridge" filter medium. Nowhere in the patent is propylene glycol mentioned -- and the heater would be insufficient to reach vaporization temperature in any case.

All the components of the PV were thus proven and firmly in place since 1940, but the technology to make it small enough to be truly personal and portable didn't exist until now. And now you see what Mr. Hon happened upon -- not merely a nicotine replacement, but a personal, portable germ-killing air sterilizer! Could there be a better accessory for the twenty-first century? The problem is, the marketing and advertising is all wrong. The PV is the diametric opposition to cigarettes -- vaping makes you healthier! -- but the nicotine issue has regulating agencies in a quandry, since they are unable to divorce nicotine from tobacco.

In fact, e-juice requires no nicotine at all; it is perfectly possible to vape pure propylene glycol. There is no psychopharmalogic effect, no flavor -- just a cool misty vapor that, in itself, is rather refreshing.

But, taking into account the benefits of the vapor itself, (and even if it is used with nicotine, it's not as addictive and sans the deleterious effects of tobacco,) is it as visually impactful and elegant as tobacco? Does it fulfill the role of the preoccupative hobby? Above all, is it enjoyable?

The answer is an unqualified yes, in all points. The act of vaping produces a thick visible glycol vapor that when exhaled, looks and behaves like tobacco smoke. It dissipates quickly -- so no smoke-filled room effect -- it presents no lingering odor, and is unstaining.

The process of vaping involves both replacing batteries and re-filling or replacing cartridges, or alternately "dripping" directly onto the atomizer. This necessitates carrying a cigarette-case-sized accessory box with these items, and gives the vaper just as much to do with his hands as a pipe-smoker.

Although Lik Hon's original design for PVs were meant to perfectly duplicate the appearance of "real" (or as vapers call them, "analog") cigarettes, vapers soon realized there is absolutely no reason for a PV to look like a tobacco product at all. There are now a large number of "modders," who enjoy taking PV components and cosmetically changing their appearance or improving their efficiency. Some craftsmen have taken PV technology and gone the other direction, incorporating it into very traditional pipes. The technology is so basic and standardized, it is entirely possible for the average home electrical hobbyist to make a PV entirely "from scratch." Amateur mixologists enjoy customizing their own non-nicotine e-juice: for propylene glycol is a natural medium for perfumes and flavorings. Any soluble candy-maker's flavors can be added and mixed for a wide variety of tastes, from coffee, to crème de menthe, to strawberry cheesecake, to chocolate.

As with beginning any new and unfamiliar endeavor, the most difficult step is the first one. The choices seem to be bewildering. Remember that all commercial PVs are extentions of only a handful of distinct designs produced by only a few manufacturers. Here's a good summary of the different styles.

The all-important question of choosing a "starter PV" has been handily addressed by the good folks at e-cigarette-forum.com, which is the world's best online compendium of all things vaporizational. They recommend the mid-size 510 series, and I agree with them. The aforementioned e-cigarette-forum has a wealth of information at all levels of use and expertise. Most of the folks there are former heavy analog smokers that have switched to vaping, with a good cross-section of working folks, scientists, doctors, and mad-scientist modders.

Do I think these PVs are a world-altering paradigm changer? You bet. But not because they are nicotine replacement therapy. That's looking through the wrong end of the telescope. Dr Oswald Robertson may not have foreseen a world in 1943 where "mankind could live...continuously in an atmosphere of glycol vapor," but that future is here, now, and we can all take a swipe at airborne respiratory diseases. If you're not a smoker, just don't use the nicotine juice; vape propylene glycol. Vape all you want, of the most delicious juice you can mix, and look stunning while doing it. It's the "new smoking," and it can be every bit as elegant as it was in 1940. And a whole lot healthier.

Click here to go to the next essay chronologically.

Click here to go back to Part Three of The Essential Accessory.

Click here to go back to Part One of The Essential Accessory.

Click here to go back to the beginning.

Click here to go to the next essay chronologically.

Click here to go back to Part Three of The Essential Accessory.

Click here to go back to Part One of The Essential Accessory.

Click here to go back to the beginning.